Table of Contents

Nestled within the steamy green hills of the Hellisheiði lava plateau, a half hour drive east of Reykavík in Southern Iceland, is a hub of futuristic industrial activity.

Harnessing the heat from the nearby Hengill volcano, Iceland’s largest geothermal plant delivers district heating to the South and West of the country. It also produces renewable electricity, which is now being used nearby to power ‘Orca’ and ‘Mammoth’.

These are the names for Climeworks’ direct air capture facilities – warehouse-like buildings surrounded by towering walls of fans and solvent filters that promise to extract carbon dioxide out of ambient air.

Mammoth was funded through $650 million from various private equity and investment management companies early in 2022. Yet a glance over Climeworks’ website could give the impression that the company is instead funded through selling carbon removal by the tonne or kilogram.

Various banners advertise subscription services where a monthly fee equates to a set amount of carbon dioxide removal. This starts at $1.20 per kilogram, nearly 200 times the price of the average carbon offset1.

The press release announcing Mammoth says the facility “capitalizes on a very dynamic market demand – with several 10-year offtake agreements signed over the last months”. Offtake agreements are like a carbon offset, but the offsetting hasn’t happened yet (more on this later).

Until mid-September (a week after I interviewed them about it), Climeworks’ homepage carried the mysterious banner ‘Goes beyond offsets’.

Going beyond offsets?

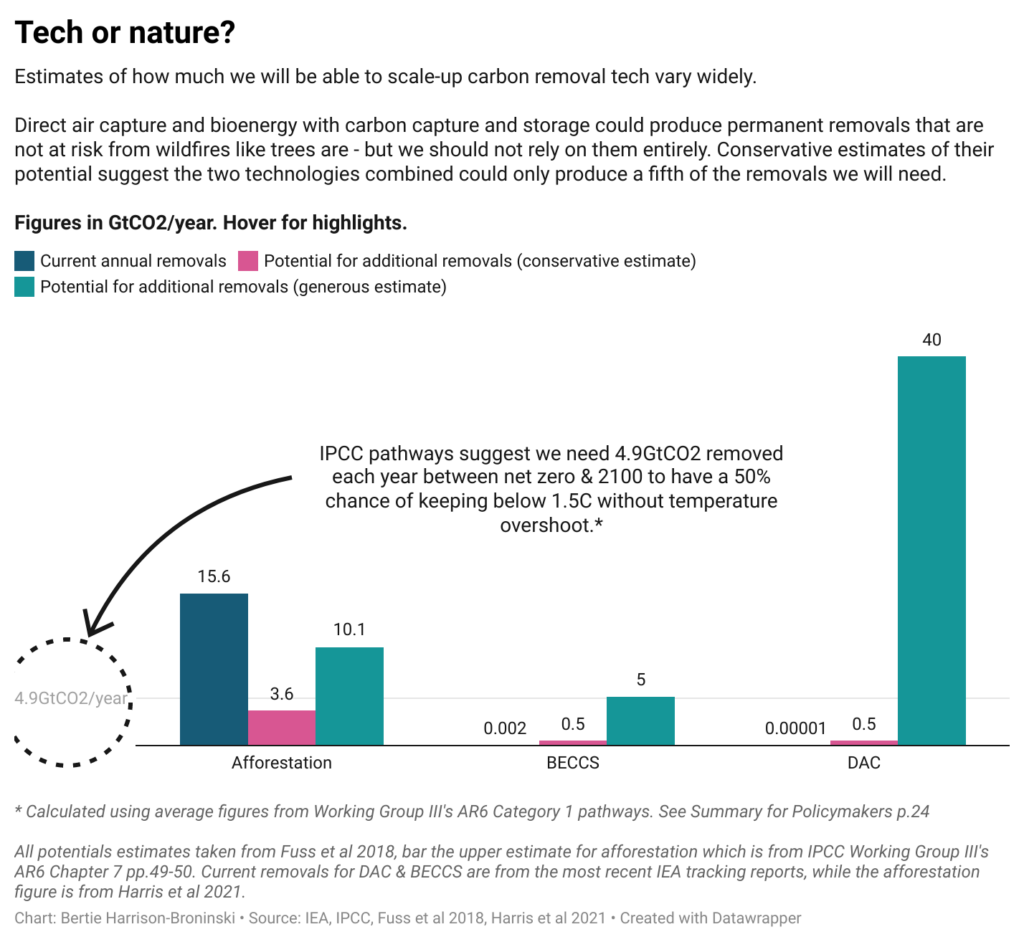

Since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a special report in 2018 outlining the need for carbon removal in gigantean volumes, ‘negative emissions’ technologies like Climeworks’ have been gaining market interest.

Hundreds of millions of dollars2 have been spent on purchasing carbon dioxide removal by the tonne since the start of the 2020s, but mostly not through the established and regulated approaches to carbon offsetting. Silicon Valley companies including Microsoft, Meta and Stripe have started a wave of offtake agreements, ex ante credits, or forward sales of carbon removal credits – all different terms for buying tonnes of carbon removal before the removal has happened.

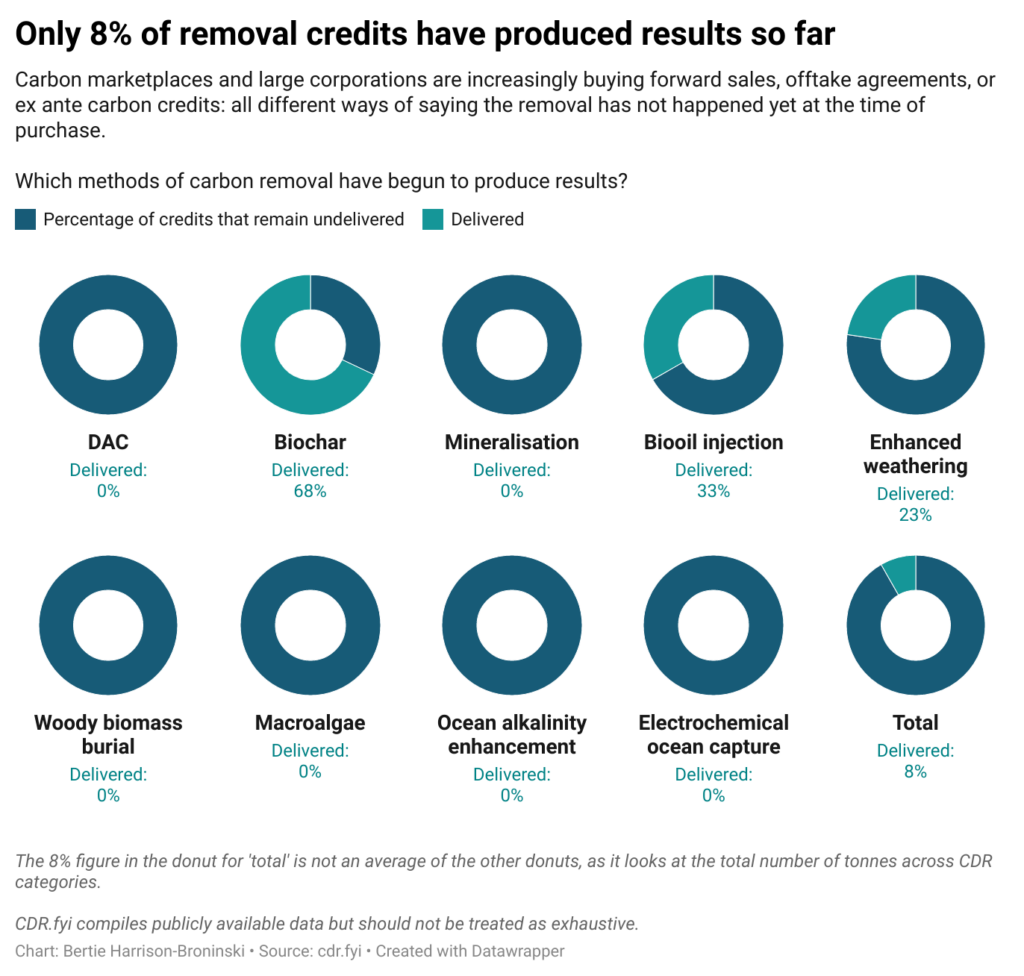

Climeworks are one of a small number of suppliers currently dominating this space. CDR.fyi, an online database of publicly announced carbon removal purchases, lists them as having sold over 49,000 tonnes of carbon removal as of the 16th December 2022. But according to the same site, not a single tonne has been delivered so far.

Currently, when companies or individuals pay for carbon offsets, they are usually buying credits for ‘avoided emissions’. The idea is that sellers change their practices around the business or land they manage to emit less CO2, and then sell a carbon credit for every tonne that they have ‘avoided’ emitting. For example, a company might decide not to cut down a forest for logging, and instead sell carbon credits. These ‘avoided emissions’ should be enabled by the revenue from the sale – if they were going to decarbonise the business anyway, they should not sell any credits.

There have been numerous issues with this system, and we are beginning to see a shift towards removal credits rather than avoided emissions. Removals do not rely on some complicated counterfactual like avoided emissions offsets. Buyers are simply paying for nature or technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it where it cannot increase global heating – ideally permanently.

A recent report from BeZero Carbon estimated that as soon as 2030, 56% of sales in the voluntary carbon market (VCM) will come from removals, a rise from only 7% today. The VCM does not include governmental emissions trading schemes: it just refers to private buyers and sellers of carbon credits.

Experts interviewed for this article, including the author of that report, Ted Christie-Miller, as well as Wijnand Stoefs and Gilles Dufrasne from Carbon Market Watch, emphasised that carbon removals have long been a part of the VCM, but only really through tree planting. Trees remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere when they respire, and store it as long as they are alive. Planting new trees then, in theory, decreases the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Afforestation is cheap, easy, and doable at scale. Despite this, it has issues – the CO2 storage is not permanent, plantations need ongoing management that cannot be guaranteed, and it is hard to anticipate future threats such as wildfires. A lot of fraudulent carbon offsetting also happens through tree-based credits. For these reasons and others, Dufrasne said that tree planting is not “credible removal”.

That’s the composition of the 7% figure, along with a very small amount of biochar, a charcoal-like material produced by heating plant matter to very high temperatures without oxygen. This aims to stop the carbon stored in plants while they were alive from returning to the atmosphere when they decompose.

The jury is still out on the permanence of this one. Dufrasne described biochar as “problematic” and “super impermanent”. Biochar scientist Dr. Manish Kumar instead suggested that the material could store carbon for anywhere between 50 and 1000 years, depending on how it is engineered, but warned that “the actual implications for the long-term application of biochar are not properly researched”.

Buy now, offset later

Tree planting is likely to stick around, but the big bucks are clearly in tech. CDR.fyi monitors all engineered removals, so that includes processes that use natural environments like biochar, enhanced weathering, and forms of ocean capture, as well as direct air capture, bio-oil injection, and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS).

At the time of writing, it lists a total of 655,864 tonnes of CO2 sold across 41 marketplaces – but only 7.2% of these have been delivered. That becomes 2.7 million tCO2 and 0.02% when the largest publicly known removal deal is included. In September, carbon marketplace Respira International agreed to buy two million tonnes of carbon removal from the controversial wood-burning company Drax once it has developed a bioenergy with carbon capture and storage plant in the USA.

Unusually for these agreements, Respira only signed a ‘memorandum of understanding’, so are not legally bound to follow through. Respira’s CEO Ana Haurie says this was because “there is still some uncertainty” around the technology, seeing as it “still has to be implemented”, but she fully intends to “enter into purchase agreement with the company” in time.

No other marketplace has announced purchases of engineered removals at this scale, never mind all in one deal. Haurie says she hopes the announcement will send a “signal that there is a market [for removals and BECCS]”.

Has that signal been received? Haurie acknowledged that there are not currently any buyers interested in these credits, saying “I think we still need some certainty around where the pricing for these credits is going to be in 2027, 2028.”

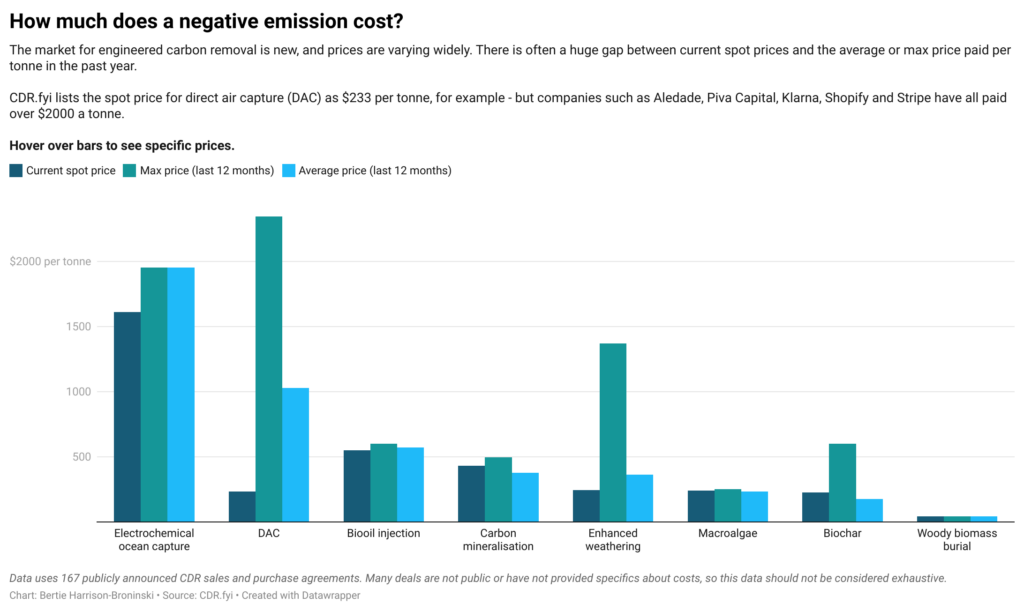

At the moment, prices vary wildly. Climeworks was charging over $1000 per tonne in July, Charm Industrial, the leaders in bio-oil injection, tend to charge around $600 a tonne, while the current spot price for woody biomass burial is $44 – less than the carbon price in the UK or EU.

A new market, or a surge in R&D?

These high and varied prices help explain why some do not consider carbon offtake agreements as being part of the voluntary market. “You really get the wrong idea when you look at the cost,” says Roger Hogland, who runs Marginal Carbon AB, a consultancy working with companies and organisations on carbon removal.

“You’re not buying tonnes. You’re giving a research and development grant in the form of buying tonnes. So that cost could be anything, could be $100,000 per tonne. You’re financing a new company [and the] deployment of a new solution. In their prototype, they’re going to remove like 100 tonnes of CO2 or something, and maybe they need to finance all their overheads, all their development costs, the researchers in their lab, etc.”

When a company like Stripe or Shopify buys “ex-ante” removal credits – meaning the sale happens before the carbon removal, often with a delivery date many years away – this should not be considered part of the offset market, in Hogland’s view.

Other experts I spoke to highlighted the fact that ex-ante deals are not fungible – you can’t trade them with other carbon credits. “If you don’t have something that you can trade, then it’s not a market, right?” said Dufrasne.

Corporate narratives around these sales tell a different story, and maybe they have a point. Framing these deals – fungible or not – as research and development funding ignores the fact that the biggest buyers are carbon marketplaces such as Puro.earth or Carbonfuture. As Ted Christie Miller said, “The ex-ante market is enormous – and there’s a lot of demand.” People have “demand” for products – corporations do not generally “demand” more opportunities to make research donations.

Ana Haurie says that Respira has “around 9% of the total removal credits available” on the market, and their income includes “significant forward sale transactions”, meaning that they are selling credits for projects that have not yet delivered. Their website and public documents discuss removal credits as a means to “compensate for one’s own historical emissions” as “Microsoft have done”, rather than primarily as an R&D funding stream.

In fact, I was unable to find any carbon removal supplier whose research and development was primarily funded through selling ex-ante carbon credits or carbon offtake agreements. In our interview, Climeworks’ carbon markets specialist Louis Uzor eventually admitted that the money from these deals was “marginal” in terms of the company’s funding.

What is almost unquestionably true is that these deals are useful in building investor confidence: Uzor, for example, implied that carbon offtake agreements with Stripe and Microsoft had been essential to winning large-scale financing.

Net Zero pledges make easy PR

Philanthropy and fungibility aside, these ex-ante deals should not be considered offsetting for the simple reason that “credits that haven’t been sequestered are not usable against your climate targets” in carbon accounting, says Christie Miller.

The effect of this is to put more focus on 2030 and 2050 targets. Unable to brand a product or service as currently carbon neutral, companies push the idea that offtake agreements will make their whole organisation carbon neutral or negative by a certain date.

It is easy to see this change in rhetoric as an improvement to the so-called “golden age of greenwashing” created by avoided emissions offsets. Several interviewees for this article praised Microsoft’s transparency around their removal programme and their due diligence in choosing projects, for example.

But is it an improvement? Corporations switching from actions to promises about the future should always raise alarm bells – it is well established in academic literature that “green discourse and pledges” by large corporations “provide the benefit of alleviating pressure from society. Not only can this generate a positive image of the company for consumers, such messages can prolong the social license to operate.”

Take Airbus for example, the largest aeronautics company in Europe. They were part of a group of aerospace manufacturers that released a joint sustainability strategy in 2019 marking offsetting as a solution for aviation emissions.

By 2021, academic studies and journalistic investigations had shown that avoided emissions credits bought by airlines were not working. One study author, Dr. Thales West, told The Guardian that many of the offsets “have no impact on the climate whatsoever”.

As airline offsetting schemes fizzled out, companies have tried different approaches. Easyjet promised to use the £25m a year they were spending on offsets to fund efficiency measures and less polluting forms of engine and fuel, for example.

Airbus instead joined the wave of Silicon Valley companies buying ex ante removal credits. In July 2022 they agreed to purchase 100,000 tCO2 per year from 1PointFive, who are building a direct air capture plant with Carbon Engineering in the US. United Airlines have also partnered with 1PointFive, and Airbus have announced that other airlines “have shown interest to collaborate with Airbus in this area with the objective to promote direct air capture as an essential pathway to achieve the industry’s net-zero target.”

100,000 tonnes is less than 0.01% of Airbus’s emissions in 2021, by their own reporting. As I have discussed in my series on CCS, there are very real limits to the scalability of direct air capture and it is highly unlikely that it will ever offset the emissions from the aviation sector.

Rather than resolving the problems with their avoided emissions offsets, these airline companies are transitioning to a different type of offsetting that cannot be similarly scrutinised until years in the future. Meanwhile, the ‘research funding’ narrative removes any obligation or political pressure to match up the money they have spent on future negative emissions with their actual emissions today.

If and when the technology is scaled up, there is not even any reason to assume that the removal market would be free of the issues that have tarred previous offsetting schemes: Dufrasne said that “all of the problems” with offsets in the past “are transferable” to removals. Christie Miller echoed this, saying “I don’t see a differentiation between the carbon dioxide removal market and the VCM” in terms of regulation.

If offsets did not work for aviation in 2020, there is no reason to assume they will with removals in 2030. One danger with these ex-ante agreements is that both parties are more invested in signalling how great their companies are going to be in a decade than they are in the actual product. Airbus and 1PointFive each helped the other become more attractive to investors, but the actual money being exchanged may be insignificant to both: 1PointFive has not announced any new construction or development as a result.

Risky business

What happens if suppliers never deliver the removals? According to Respira boss Ana Haurie, marketplaces either forward sell on a “contingent basis”, so they only deliver to clients if they have received the credits themselves, or they can give clients the right to “substitute different credits into that contract with similar characteristics”.

No one I spoke to seemed concerned that Carbon Engineering and Climeworks’ direct air capture projects would under-deliver, but it is perhaps unsurprising that Respira is showing more caution with Drax, given the poor record of attaching carbon capture tech to power stations.

A bigger risk is that Silicon Valley and these new carbon marketplaces support the wrong solutions entirely, opting for flashy innovation over sustainability or efficiency. Haurie switched from gushingly touting the tree-burning Drax deal as an act of “tree hugging” to becoming visibly flustered and evasive when I asked about Drax’s recent wave of bad press, citing allegations of environmental racism and driving deforestation.

Carbon Market Watch’s Wijnand Stoefs talked scathingly of CO2Rail’s proposal to build trains which capture CO2 from the air, describing it as “loopy and frankly a waste of time” due to issues with efficiency, materials and infrastructure needs. Stoefs highlighted various alternatives that he thought would be cheaper and more energy efficient, but the project has had backing from the Musk Foundation and a steady stream of glowing press coverage.

Academics have long worried that carbon markets could distract companies from the most impactful decarbonisation work in favour of cheaper or more PR-friendly options. A 2020 study calculated this alone could increase global heating by up to 1.4°C.

Markets are not everything

It is still early days for removal markets and a lot is likely to change. Microsoft’s 2022 report on carbon removal stated that “the market lacks strong, common definitions and standards” and supply is still “limited and expensive”. The landscape will shift, depending on how these issues are addressed. In the past two months, new removal markets have launched that follow the normal approach of the VCM, such as Salesforce’s Net Zero Marketplace, as well as new models, such as London Stock Exchange’s marketplace that sells shares in suppliers, which then give carbon credits as dividends.

Regardless, “the voluntary market is never going to be anywhere close to what we need to reach the several gigaton level of carbon removal [we need] to reach global climate targets,” says Hogland. Uzor echoed this, making clear that Climeworks does not think the private sector can fund our way to net zero without government involvement: “a requirement to reach gigatonne scale capture rates by the mid-century heavily relies on public sector regulation, incentives, some sort of policy mechanism to really bring that uptake.”

As ActionAid’s Kelly Stone said on our podcast, “it’s too early to give up” on carbon removal markets. “In the history of carbon markets, they have done far more harm than good. That does not mean that we cannot make a difference by pushing for transparency, and for changes that limit the harm. I do believe that can make a difference. But we should be honest about what carbon markets are, and they aren’t a solution.”

Bertie Harrison-Broninski is an Assistant Editor of the Land and Climate Review, and a researcher studying bioenergy and BECCS policy for Culmer Raphael. He is also a freelance investigative journalist, with recent work including Al Jazeera’s Degrees of Abuse series and John Sweeney’s recent book on Ghislaine Maxwell. Find him on twitter @bertrandhb.

Endnotes

[1] According to Trove Research, on average carbon credits for avoided emissions were $6.40 per tonne in October 2022.

[2] At the time of writing, CDR.fyi lists $210,949,700 total sales of engineered carbon removal by the tonne. This will be lower than the true figure, as it just includes the publicly announced purchases that have been logged by the researchers and analysts who run the site. Not all purchase agreements logged on the site include the cost (as this is not always announced), and as one contributor told me, there may well be “hidden deals” that are yet to be announced. He estimated that the site covers “75% of the volume and value”, but stressed that we cannot know.

Read more:

- Removals